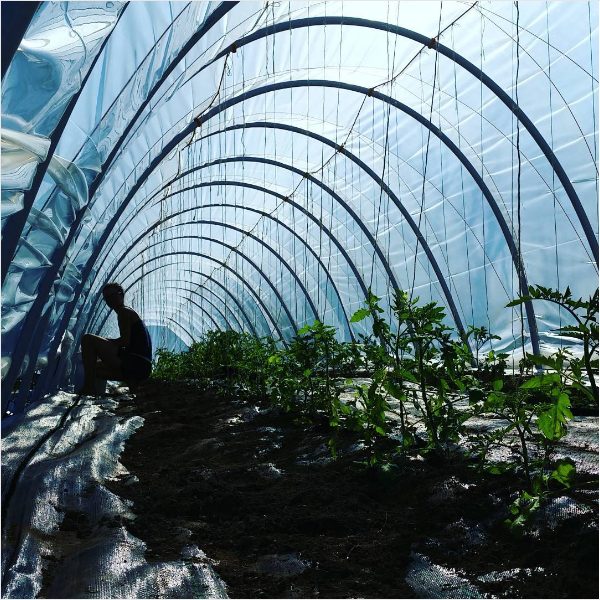

Winter has finally afforded a chance to look back at last year's SARE grant, and it's fair to say that the experiment produced some interesting results. The field looks a whole lot more white right now than the photo to the left.

To recap, the scope of my research grant was to look into the use of spent brewers' grain - the main byproduct of beer production - as a soil amendment for crop production. I was investigating, in particular, a way to prevent the spent grains from going quickly anaerobic, which any farmer or home gardener can tell you is not ideal. You can read more about the bokashi composting process in the previous two blog posts.

It was a remarkably slow fruiting season for us in Maine last year, but a yield increase of 26-29% was noted in the experimental bSBG/SBG huskcherry groups over the control, respectively. I'm unsure, though, if the yield increases were a result of greater fruit set. The experimental groups certainly grew more vigorously (see the previous blog post for photos), but a surprising thing happened when the fall frosts settled in earnest in autumn. The bSBG/SBG huskcherries fared far better while the control withered, allowing almost a month longer for ripening of harvestable fruit. This, despite all three being under the same frost protection row cover.

This image shows the control huskcherries [right] compared next to the SBG experimental group [left] after the second frost in October. A few errant kale plants in front of the control give a misleading sense of the control's vibrancy.

So, was the yield increase the result of plant size and fruit set or the longer harvest season? And what is it that the huskcherries were able to take into their bodies from the SBGs that offered greater frost protection? Not sure, but it sure feels good to come away with a few more questions.

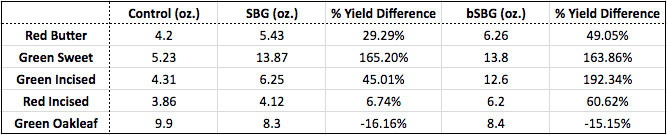

As for the Salanova, all but one the varieties showed increases in yield. The % yield difference of the compared to the control group is suggestive, but varied more widely than I feel comfortable drawing solid conclusions from. It was a mistake, I think, to try to grow multiple varieties of Salanova versus a single variety of head lettuce. My hope was to gain efficiency by combining my farm's crop production with the grant research, but instead it complicated the experiment. A good lesson on the importance of limiting the scope of future experiments.

I took soil samples as a final piece of last year's work to compare to the spring test results, which together give some indication of the qualities of spent brewers' grains and their lasting effect in soil. Important to consider using these results is that the spring soil tests were taken only a week after SBG/bSBG incorporation.

The spring tests show an increase in phosphorus, magnesium, nitrogen, manganese, and zinc, as well as .5-1.5% increase in organic matter, and a 2-4% increase in cation exchange capacity [CEC]. For those unfamiliar, CEC is a measure of a soil's ability to hold positively-charged nutrients. One way to think about it is that CEC is a storehouse plants, microbiology, and fungi draw on for their growth. The soil test results also show a decrease in potassium versus the control, and mixed results for calcium and sulfur levels.

The post-harvest soil tests indicate the following about using SBGs as a soil amendment:

- End of the season testing show strong measures of increase of phosphorus, manganese, zinc, and OM in the soil. Magnesium trended towards increased levels in the soil.

- Some tests – for potassium, iron, sulfur, and CEC – showed mixed results of both increases and decreases that would benefit from further study.

- Soil pH showed increases, but I believe this is likely a result from lime applied in 2016. This is supported by the fact that the pH control groups also increased during the season.

- Finally, and curiously, where calcium levels showed a decrease in the experimental SBG plots, the levels in the bSBG plots showed increases [+9#/ac. and +60#/ac.].

So, this is where things stand with the experiment. It's certainly an amendment I intend to continue working with, and the bokashi composting process proved to be an excellent way to stabilize the SBGs for use on the farm. The 55-gallon drums were an easy way to transport and inoculate the grains. What I'm interested in now is sending samples off of SBGs and bSBGS for direct analysis at the University of Maine. Having a more precise sense of the constituent parts of the spent brewers' grain is critical for myself, and hopefully other farmers, to make informed choices as to an appropriate application rate based on soils' needs.